News: Check out “Into the Forest”, new nature documentary about the reptiles and amphibians of central Europe.

If it weren’t for the Cold War I’d never get to go herping in the rolling hills of southwestern Germany. My dad was a US Army officer stationed in Germany where he met my mom. Then they had me as it were. Because my mom’s side of the family still lives there I get to have a beautiful place to visit. This blog is about the forest near where my family lives. I’ve been exploring it since my Opa used to take me there in a stroller.

My family lives in the small town of Denkendorf in Baden-Württemberg. It’s a typicall European town with red tile roofs, where family bakeries, produce stores and butchers still proliferate. Like many German towns, Denkendorf is surrounded by forests, meadows, and agriculture. Though Germany doesn’t have many swaths of wilderness left like in the US, the trade-off is that every town is surrounded by nature. The beauty of this setting is that you can step out your door and be hiking through the forest within minutes without the need to drive there.

My aunt and uncle, where I stay, live right on the edge of town along the farm fields that I walk through on my way to the forest. The fields are small family farms interspersed with paved foot paths. The public is free to wander along the rows of purple lettuce, asparagus, strawberries, and cabbage. Among the fields are small orchards with crooked, moss-covered apple tress, and old farm machinery. On the surface it’s a simple, old fashioned operation.

I can’t think of any equivalent setting in America because big ag and private property mostly preclude it. This old world layout also emerged centuries ago before the automobile-based society. The foot paths are never-ending throughout the entire country; you could hike from Stuttgart to Berlin through continuous fields, forests and villages. While wandering through the fields, the first animal that I spot every day is the “Milane” or Red-kite soaring above. It’s a large raptor that looks more exotic and ghostly than normal hawks because of the way it flies with bent wings and a scissored tail.

After about 15 minutes walking through the fields I reach the forest where herping begins. If you could go herping anywhere on Earth, Germany shouldn’t logically be high on your list because it’s not very specious. Many US states have well-over 100 herp species. In some spots you can realistically encounter 30 species in a day. Germany has a total of 20 species, and you can only find a handful of species at any given spot. But the reptiles and amphibians that do live in Germany are exceptionally interesting and beautiful. The density of many species is so high that you can find them all day long and observe their variation of patterns.

In 2014 I found this deformed Fire Salamander with 6 toes instead of 5, appearing as if a second foot partially formed.

The forest where I go is called Alter Eichwald, or “Old Oak Forest”. Even though I go years between visits to Germany, I’ve been exploring this forest for so long that I know every forest pond, and where every ephemeral rivulet flows in spring. This helps me find concentrations of the beautiful Fire Salamander, my favorite animal. This big Salamander has glossy black skin with bold yellow spots to warn of its mild toxicity. The Fire Salamander looks every bit a character from a fairy-tale in which the animals talk.

Fire Salamanders occur here in a specific micro habitat. They live around deciduous trees, not conifers, with rivulets nearby where females deposit their live young. If you peer into the tiny streams at the right time of year you might see dozens of tiny Fire Salamander larvae. There’s also usually Bärlauch, or “Bear’s Garlic” growing around where Fire Salamanders live. This beautiful Wild Leek covers the forest floor with its sheathing green leaves and makes the whole forest smell like garlic.

Fire Salamanders are extremely abundant in this forest, which can’t be said for the rest of Europe. Elsewhere, particularly the Netherlands, they’ve gone extinct or are teetering on the edge of survival. Most amphibian lovers know of the global Chytrid fungus plague that has already killed off around 150 amphibian species. But Fire Salamanders are being ravaged by yet another, newly discovered species of fungus named Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans. Once fungus spores embed on the Salamanders’ skin they essentially destroy the skin and kill the animal. There’s little resistance among Fire Salamanders, and nothing to stop the fungus from spreading. Once the fungus broadens its range into another forest, the Fire Salamanders there are as good as dead. There’s evidence that it arrived from Asia with the pet trade on the skin of resistant newts. That suggests that the least we can do to prevent the spread of killer amphibian fungus is to not buy amphibians from pet stores, and certainly never release them into the wild.

Every time I come back to Germany I’m apprehensive to search for Fire Salamanders, fearing that I won’t find them again. There’s no resounding reason that the fungus hasn’t arrived here yet, and I fear that it’s “when” rather than “if”. I feel great relief and joy when I start finding them under logs.

Decades ago, massive forestry machinery gouged deep tire tracks into the muddy forest floor at one particular spot. They’ve remained, and have since become small ponds in the middle of the forest. I still remember when they were fresh tracks when I was a teenager. After spring rains, hundreds of Alpine Newts converge into the water of these tire tracks to breed. The Alpine Newt is a most unlikely looking creature with stripes of turquoise, fire-orange, and leopard spots. A few years ago I wanted to photograph the Newts in a natural looking underwater setting, and the only way to accomplish that was to collect a few and bring them back to an aquarium. I filled the aquarium with leaves to make it look natural. The Newts readily began eating worms and even mating in the simulated pond. I returned them to their tire tracks immediately after photographing. Today the tire tracks still hold a bit of water, but have succumb to pond succession where years of forest debris have filled them. I’m surprised they’ve lasted this long.

Similar to the tire tracks, decades ago a digger excavated a small pond in a meadow on the edge of the forest to create animal habitat or a “Biotope”. It permanently filled with rain water and became brimming with life during only its first spring. I remember visiting the Biotope at about 13 and being mesmerized by all the cool animals living there. At that time the water was deep and clear, and the banks of the pond were open and sunny. It was filled with thousands of tadpoles, 2 Newt species, 3 Toad and Frog species, and Grass Snakes. These days when I return to the Biotope it’s a sober reminder of how quickly time progresses. It’s almost filled back in with debris with only a few inches of water remaining. Full grown trees have since grown up around the pond and shaded it. There’s no doubt still life within its waters, but only an echo of what once thrived here.

This forest is a nature preserve, or “Naturschutzgebiet”. To the untrained eye it may look pristine, but it’s also logged for timber. Selection cuts are used instead of clear cuts, which helps keep the ecosystem intact. A love of nature and hiking through the forest are integral parts of the local culture. Because of this, there’s great emphasis on preserving the forest as an inviting refuge for people to come and wander. But much like in the rest of the world, the old generation is mainly who values the forest. Fewer younger Germans spend much time in the forest, and from my experience, have any knowledge of the nature around them. Social media has taken precedence.

On the edge of the forest there’s another sunny wildflower meadow where an old apple orchard grows. There are a lot of interesting things to be found here. Laughter and screams from playing children come from the other side of the meadow. It’s the “Waldkindergarten”, or Forest Kindergarten, where the kids spend their class day outside, rain or shine, with just a little log hut as the school building. Parents walk their children into the forest every morning, and they must be immunized for tick bites.

In the middle of the meadow sits a row of bustling bee hives where “Waldhonig”, or forest honey is made. I’ve come into this sunny place in search of the beautiful Sand Lizard. Looking at the hives I think to myself, “If I were a lizard I’d favor such an open basking spot with food buzzing around.” Sure enough, when I got closer I spotted a mated pair of intertwined Sand Lizards basking on the corner of a hive. I almost didn’t believe it. The male was the most vibrant green specimen I’ve ever seen. Amazingly, they sat there long enough for me to switch lenses and take a good shot. They even leapt up to catch flying bees. It was surreal to stand in between these stacked hives in a cloud of whizzing bees while they were indifferent to my presence.

Whenever I visit in Spring there are constant rustles in the leaves as I walk through the forest. It’s usually one of three creatures; a Common Frog, a Shrew or less often, a Slow Worm. The Slow Worm, or “Blindschleiche” is a legless lizard with an extremely smooth, shiny body that’s often mistaken for a snake. Like many lizards, their tail is very fragile and breaks off when grabbed. The tail then twitches to attract the attention of their attacker while the slow worm attempts to escape. It’s an effective defense because it forces the predator to choose between the easy meat of a twitching tail, or a fleeing lizard that would require more energy to catch again. The tail regrows, but shorter and discolored. Every Blindschlieche that I’ve ever found has had a regrown tail.

This blog would never end if I wrote about every animal that I’ve ever encountered in the Alter Eichwald, but I at least want to mention some others. The amount of life in the forest is surprising given the nearby cities and population density. I’ve encountered badgers, whose presence is revealed by large holes in hillsides with freshly dug dirt strewn around. Hedgehogs are very common in the area, and even in peoples’ gardens. Being nocturnal, they’re rarely seen, but their shiny little turds are proof of their existence each new morning. Some of the other common characters that I see, but haven’t photographed are the Beech Marten, Eurasian Jay, Viviparous Lizard, and Roe Deer.

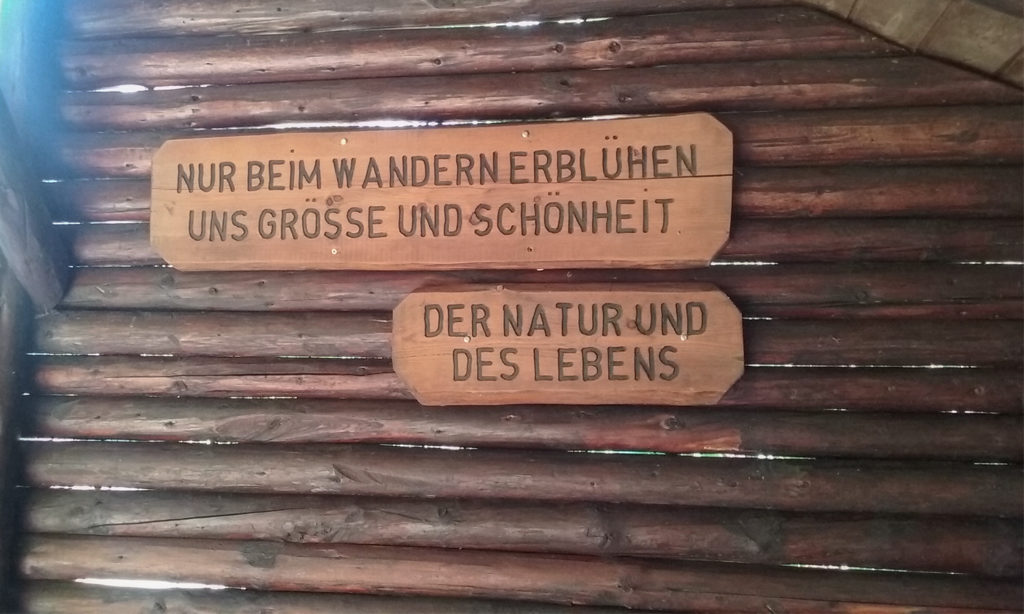

A plaque in a small weather shelter in the forest. “Only when wandering does the greatness and beauty of nature and life blossom”

Back in 2009 I produced the little nature documentary below about my travels through the forest, and Fire Salamander and Alpine Newt. I filmed it on one of my regular 2 week trips to visit my aunt and uncle. Serendipitously, my now friend Markus Bühler found the video and contacted me. He lives nearby in Rottenburg and offered take me to some great great herping spots whenever I visit Germany.

On my visit in 2017 we went on 2 particularly awesome excursions. One was near Tübingen to find the introduced Green Lizards, and the other was into the Black Forest in search of the Black Hell Adder (a melanistic morph of the European Common Adder).

Hi,

My grandson is in Germany with his parents. He is very interested in salamanders. After watching and recommending your video to him-he’s ten-I’m wondering if you know of any guided tours to find reptiles like the fire salamander. They will be in the country through the spring of 2019. If you are familiar with any family oriented tours, I would love to know about them. Thank you so much.

Hi Nancy, Good question, but I don’t know of any such tours.